library(tidyverse)

library(RSQLite)

library(scales)

library(slider)

library(furrr)Beta Estimation

You are reading Tidy Finance with R. You can find the equivalent chapter for the sibling Tidy Finance with Python here.

In this chapter, we introduce an important concept in financial economics: the exposure of an individual stock to changes in the market portfolio. According to the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) of Sharpe (1964), Lintner (1965), and Mossin (1966), cross-sectional variation in expected asset returns should be a function of the covariance between the excess return of the asset and the excess return on the market portfolio. The regression coefficient of excess market returns on excess stock returns is usually called the market beta. We show an estimation procedure for the market betas. We do not go into details about the foundations of market beta but simply refer to any treatment of the CAPM for further information. Instead, we provide details about all the functions that we use to compute the results. In particular, we leverage useful computational concepts: rolling-window estimation and parallelization.

We use the following R packages throughout this chapter:

Compared to previous chapters, we introduce slider (Vaughan 2021) for sliding window functions, and furrr (Vaughan and Dancho 2022) to apply mapping functions in parallel.

Estimating Beta Using Monthly Returns

The estimation procedure is based on a rolling-window estimation, where we may use either monthly or daily returns and different window lengths. First, let us start with loading the monthly CRSP data from our SQLite-database introduced in Accessing and Managing Financial Data and WRDS, CRSP, and Compustat.

tidy_finance <- dbConnect(

SQLite(),

"data/tidy_finance_r.sqlite",

extended_types = TRUE

)

crsp_monthly <- tbl(tidy_finance, "crsp_monthly") |>

select(permno, date, industry, ret_excess) |>

collect()

factors_ff3_monthly <- tbl(tidy_finance, "factors_ff3_monthly") |>

select(date, mkt_excess) |>

collect()

crsp_monthly <- crsp_monthly |>

left_join(factors_ff3_monthly, join_by(date))To estimate the CAPM regression coefficients

\[

r_{i, t} - r_{f, t} = \alpha_i + \beta_i(r_{m, t}-r_{f,t})+\varepsilon_{i, t}

\] we regress stock excess returns ret_excess on excess returns of the market portfolio mkt_excess. R provides a simple solution to estimate (linear) models with the function lm(). lm() requires a formula as input that is specified in a compact symbolic form. An expression of the form y ~ model is interpreted as a specification that the response y is modeled by a linear predictor specified symbolically by model. Such a model consists of a series of terms separated by + operators. In addition to standard linear models, lm() provides a lot of flexibility. You should check out the documentation for more information. To start, we restrict the data only to the time series of observations in CRSP that correspond to Apple’s stock (i.e., to permno 14593 for Apple) and compute \(\hat\alpha_i\) as well as \(\hat\beta_i\).

fit <- lm(ret_excess ~ mkt_excess,

data = crsp_monthly |>

filter(permno == "14593")

)

summary(fit)

Call:

lm(formula = ret_excess ~ mkt_excess, data = filter(crsp_monthly,

permno == "14593"))

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.5173 -0.0563 0.0001 0.0605 0.3949

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 0.01018 0.00498 2.05 0.041 *

mkt_excess 1.38424 0.10903 12.70 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 0.112 on 514 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.239, Adjusted R-squared: 0.237

F-statistic: 161 on 1 and 514 DF, p-value: <2e-16lm() returns an object of class lm which contains all information we usually care about with linear models. summary() returns an overview of the estimated parameters. coefficients(fit) would return only the estimated coefficients. The output above indicates that Apple moves excessively with the market as the estimated \(\hat\beta_i\) is above one (\(\hat\beta_i \approx 1.4\)).

Rolling-Window Estimation

After we estimated the regression coefficients on an example, we scale the estimation of \(\beta_i\) to a whole different level and perform rolling-window estimations for the entire CRSP sample. The following function implements the CAPM regression for a data frame (or a part thereof) containing at least min_obs observations to avoid huge fluctuations if the time series is too short. If the condition is violated, that is, the time series is too short, the function returns a missing value.

estimate_capm <- function(data, min_obs = 1) {

if (nrow(data) < min_obs) {

beta <- as.numeric(NA)

} else {

fit <- lm(ret_excess ~ mkt_excess, data = data)

beta <- as.numeric(coefficients(fit)[2])

}

return(beta)

}Note that the tidyfinance package provides an estimate_model() function that provides more flexibility with respect to the model.

Next, we define a function that does the rolling estimation. The slide_period function is able to handle months in its window input in a straightforward manner. We thus avoid using any time-series package (e.g., zoo) and converting the data to fit the package functions, but rather stay in the world of the tidyverse.

The following function takes input data and slides across the date vector, considering only a total of months months. The function essentially performs three steps: (i) arrange all rows, (ii) compute betas by sliding across months, and (iii) return a tibble with months and corresponding beta estimates. As we demonstrate further below, we can also apply the same function to daily returns data.

roll_capm_estimation <- function(data, months, min_obs) {

data <- data |>

arrange(date)

betas <- slide_period_vec(

.x = data,

.i = data$date,

.period = "month",

.f = ~ estimate_capm(., min_obs),

.before = months - 1,

.complete = FALSE

)

return(tibble(

date = unique(data$date),

beta = betas

))

}Before we attack the whole CRSP sample, let us focus on a couple of examples for well-known firms.

examples <- tribble(

~permno, ~company,

14593, "Apple",

10107, "Microsoft",

93436, "Tesla",

17778, "Berkshire Hathaway"

)If we want to estimate rolling betas for Apple, we can use mutate(). We take a total of 5 years of data and require at least 48 months with return data to compute our betas. Check out the Exercises if you want to compute beta for different time periods.

beta_example <- crsp_monthly |>

filter(permno == examples$permno[1]) |>

mutate(roll_capm_estimation(

pick(date, ret_excess, mkt_excess),

months = 60, min_obs = 48)

) |>

drop_na()

beta_example# A tibble: 469 × 6

permno date industry ret_excess mkt_excess beta

<dbl> <date> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 14593 1984-12-01 Manufacturing 0.170 0.0184 2.05

2 14593 1985-01-01 Manufacturing -0.0108 0.0799 1.90

3 14593 1985-02-01 Manufacturing -0.152 0.0122 1.88

4 14593 1985-03-01 Manufacturing -0.112 -0.0084 1.89

5 14593 1985-04-01 Manufacturing -0.0467 -0.0096 1.90

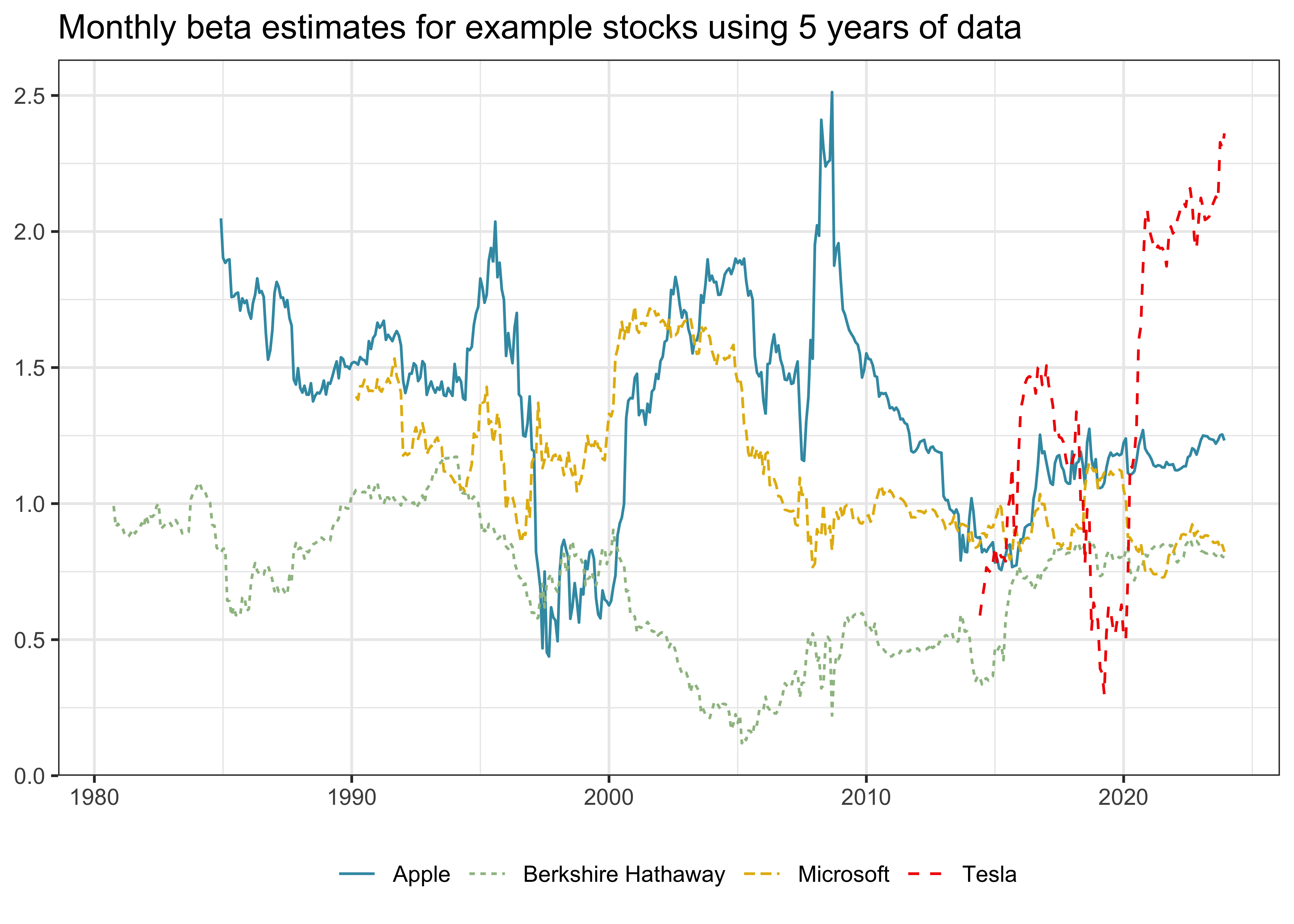

# ℹ 464 more rowsIt is actually quite simple to perform the rolling-window estimation for an arbitrary number of stocks, which we visualize in the following code chunk and the resulting Figure 1.

beta_examples <- crsp_monthly |>

inner_join(examples, join_by(permno)) |>

group_by(permno) |>

mutate(roll_capm_estimation(

pick(date, ret_excess, mkt_excess),

months = 60, min_obs = 48)

) |>

ungroup() |>

select(permno, company, date, beta) |>

drop_na()

beta_examples |>

ggplot(aes(

x = date,

y = beta,

color = company,

linetype = company)) +

geom_line() +

labs(

x = NULL, y = NULL, color = NULL, linetype = NULL,

title = "Monthly beta estimates for example stocks using 5 years of data"

)Parallelized Rolling-Window Estimation

Even though we could now just apply the function using group_by() on the whole CRSP sample, we advise against doing it as it is computationally quite expensive. Remember that we have to perform rolling-window estimations across all stocks and time periods. However, this estimation problem is an ideal scenario to employ the power of parallelization. Parallelization means that we split the tasks which perform rolling-window estimations across different workers (or cores on your local machine).

First, we nest() the data by permno. Nested data means we now have a list of permno with corresponding time series data and an industry label. We get one row of output for each unique combination of non-nested variables which are permno and industry.

crsp_monthly_nested <- crsp_monthly |>

nest(data = c(date, ret_excess, mkt_excess))

crsp_monthly_nested# A tibble: 30,508 × 3

permno industry data

<dbl> <chr> <list>

1 10000 Manufacturing <tibble [16 × 3]>

2 10001 Utilities <tibble [378 × 3]>

3 10002 Finance <tibble [324 × 3]>

4 10003 Finance <tibble [118 × 3]>

5 10005 Mining <tibble [65 × 3]>

# ℹ 30,503 more rowsAlternatively, we could have created the same nested data by excluding the variables that we do not want to nest, as in the following code chunk. However, for many applications it is desirable to explicitly state the variables that are nested into the data list-column, so that the reader can track what ends up in there.

crsp_monthly_nested <- crsp_monthly |>

nest(data = -c(permno, industry))Next, we want to apply the roll_capm_estimation() function to each stock. This situation is an ideal use case for map(), which takes a list or vector as input and returns an object of the same length as the input. In our case, map() returns a single data frame with a time series of beta estimates for each stock. Therefore, we use unnest() to transform the list of outputs to a tidy data frame.

crsp_monthly_nested |>

inner_join(examples, join_by(permno)) |>

mutate(beta = map(

data,

\(x) roll_capm_estimation(x, months = 60, min_obs = 48)

)) |>

unnest(beta) |>

select(permno, date, beta_monthly = beta) |>

drop_na()# A tibble: 1,509 × 3

permno date beta_monthly

<dbl> <date> <dbl>

1 10107 1990-03-01 1.39

2 10107 1990-04-01 1.38

3 10107 1990-05-01 1.43

4 10107 1990-06-01 1.43

5 10107 1990-07-01 1.45

# ℹ 1,504 more rowsHowever, instead, we want to perform the estimations of rolling betas for different stocks in parallel. If you have a Windows or Mac machine, it makes most sense to define multisession, which means that separate R processes are running in the background on the same machine to perform the individual jobs. If you check out the documentation of plan(), you can also see other ways to resolve the parallelization in different environments. Note that we use availableCores() to determine the number of cores available for parallelization, but keep one core free for other tasks. Some machines might freeze if all cores are busy with Python jobs.

n_cores = availableCores() - 1

plan(multisession, workers = n_cores)Using eight cores, the estimation for our sample of around 25k stocks takes around 20 minutes. Of course, you can speed up things considerably by having more cores available to share the workload or by having more powerful cores. Notice the difference in the code below? All you need to do is to replace map() with future_map().

beta_monthly <- crsp_monthly_nested |>

mutate(beta = future_map(

data, \(x) roll_capm_estimation(x, months = 60, min_obs = 48)

)) |>

unnest(c(beta)) |>

select(permno, date, beta_monthly = beta) |>

drop_na()If you want to implement the above estimation steps using the tidyfinance package, then you can use the estimate_betas() function:

beta_monthly <- crsp_monthly |>

estimate_betas(model = "ret_excess ~ mkt_excess", lookback = months(60), min_obs = 48, use_furrr = TRUE)Estimating Beta Using Daily Returns

Before we provide some descriptive statistics of our beta estimates, we implement the estimation for the daily CRSP sample as well. Depending on the application, you might either use longer horizon beta estimates based on monthly data or shorter horizon estimates based on daily returns. As loading the full daily CRSP data requires relatively large amounts of memory, we split the beta estimation into smaller chunks. The logic follows the approach that we use to download the daily CRSP data (see WRDS, CRSP, and Compustat).

First, we load the daily Fama-French market excess returns.

factors_ff3_daily <- tbl(tidy_finance, "factors_ff3_daily") |>

select(date, mkt_excess) |>

collect()We then create a connection to the daily CRSP data in our database, but we don’t load the whole table into our memory. We only extract all distinct permno because we loop the beta estimation over batches of stocks.

crsp_daily_db <- tbl(tidy_finance, "crsp_daily")

permnos <- crsp_daily_db |>

distinct(permno) |>

pull(permno)For the daily data, we consider around three months of data, require at least 48 observations, and estimate betas in batches of 500.

batch_size <- 500

batches <- ceiling(length(permnos) / batch_size)We then proceed to perform the same steps as with the monthly CRSP data, just in batches: Load in daily returns, nest the data by stock, and parallelize the beta estimation across stocks.

beta_daily <- list()

for (j in 1:batches) {

permno_batch <- permnos[

((j - 1) * batch_size + 1):min(j * batch_size, length(permnos))

]

crsp_daily_sub <- crsp_daily_db |>

filter(permno %in% permno_batch) |>

select(permno, date, ret_excess) |>

collect()

crsp_daily_sub_nested <- crsp_daily_sub |>

inner_join(factors_ff3_daily, join_by(date)) |>

mutate(date = floor_date(date, "month")) |>

nest(data = c(date, ret_excess, mkt_excess))

beta_daily[[j]] <- crsp_daily_sub_nested |>

mutate(beta_daily = future_map(

data, \(x) roll_capm_estimation(x, months = 3, min_obs = 48)

)) |>

unnest(c(beta_daily)) |>

select(permno, date, beta_daily = beta) |>

drop_na()

message("Batch ", j, " out of ", batches, " done (", percent(j / batches), ")\n")

}

beta_daily <- bind_rows(beta_daily)You can also use the estimate_betas() function from the tidyfinance package to estimate betas based on daily data. Please consult the corresponding documentation and exercise below.

Comparing Beta Estimates

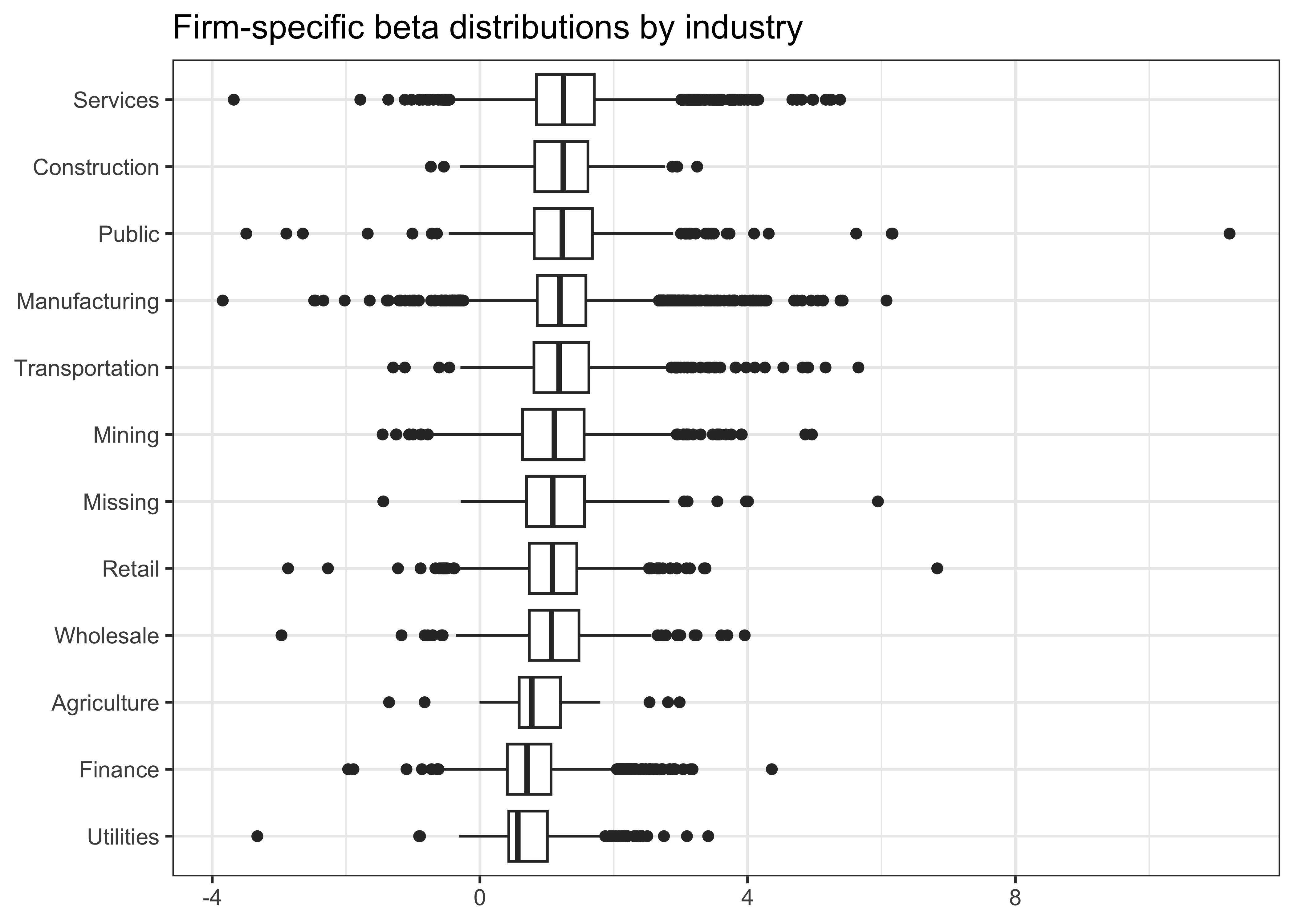

What is a typical value for stock betas? To get some feeling, we illustrate the dispersion of the estimated \(\hat\beta_i\) across different industries and across time below. Figure 2 shows that typical business models across industries imply different exposure to the general market economy. However, there are barely any firms that exhibit a negative exposure to the market factor.

crsp_monthly |>

left_join(beta_monthly, join_by(permno, date)) |>

drop_na(beta_monthly) |>

group_by(industry, permno) |>

summarize(beta = mean(beta_monthly),

.groups = "drop") |>

ggplot(aes(x = reorder(industry, beta, FUN = median), y = beta)) +

geom_boxplot() +

coord_flip() +

labs(

x = NULL, y = NULL,

title = "Firm-specific beta distributions by industry"

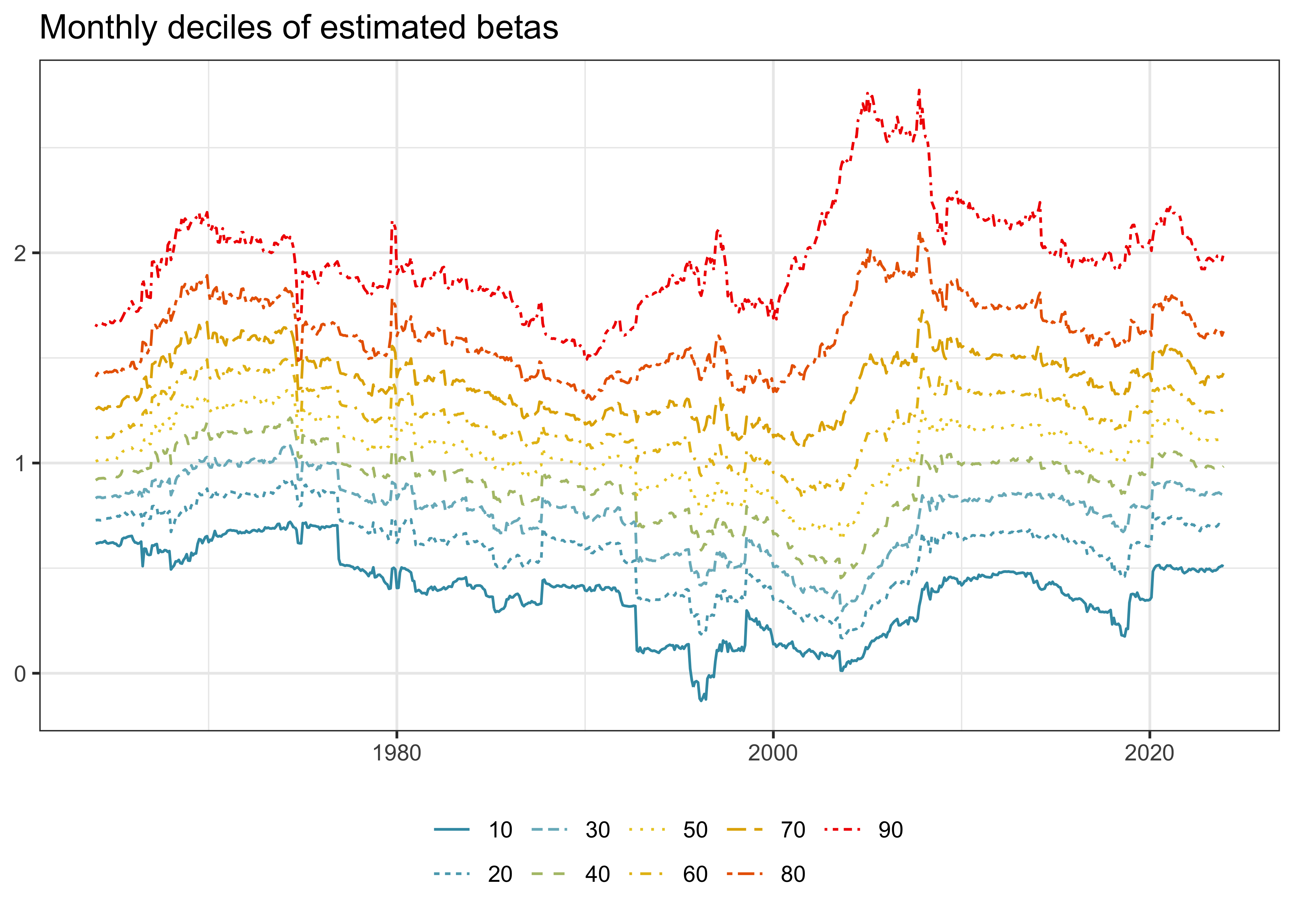

)Next, we illustrate the time-variation in the cross-section of estimated betas. Figure 3 shows the monthly deciles of estimated betas (based on monthly data) and indicates an interesting pattern: First, betas seem to vary over time in the sense that during some periods, there is a clear trend across all deciles. Second, the sample exhibits periods where the dispersion across stocks increases in the sense that the lower decile decreases and the upper decile increases, which indicates that for some stocks the correlation with the market increases while for others it decreases. Note also here: stocks with negative betas are a rare exception.

beta_monthly |>

drop_na(beta_monthly) |>

group_by(date) |>

reframe(

x = quantile(beta_monthly, seq(0.1, 0.9, 0.1)),

quantile = 100 * seq(0.1, 0.9, 0.1)

) |>

ggplot(aes(

x = date,

y = x,

color = as_factor(quantile),

linetype = as_factor(quantile)

)) +

geom_line() +

labs(

x = NULL, y = NULL, color = NULL, linetype = NULL,

title = "Monthly deciles of estimated betas",

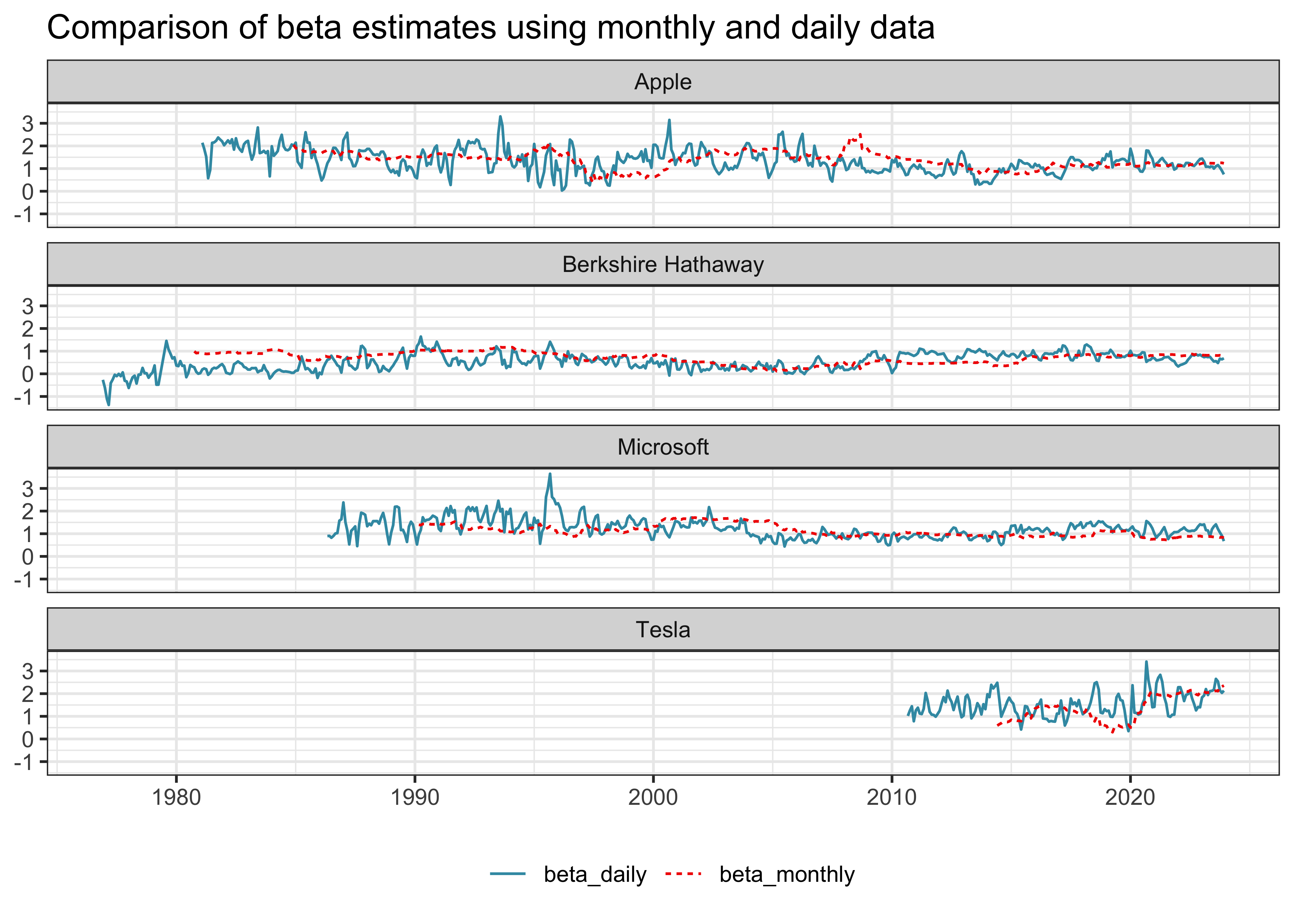

)To compare the difference between daily and monthly data, we combine beta estimates to a single table. Then, we use the table to plot a comparison of beta estimates for our example stocks in Figure 4.

beta <- beta_monthly |>

full_join(beta_daily, join_by(permno, date)) |>

arrange(permno, date)

beta |>

inner_join(examples, join_by(permno)) |>

pivot_longer(cols = c(beta_monthly, beta_daily)) |>

drop_na() |>

ggplot(aes(

x = date,

y = value,

color = name,

linetype = name

)) +

geom_line() +

facet_wrap(~company, ncol = 1) +

labs(

x = NULL, y = NULL, color = NULL, linetype = NULL,

title = "Comparison of beta estimates using monthly and daily data"

)The estimates in Figure 4 look as expected. As you can see, it really depends on the estimation window and data frequency how your beta estimates turn out.

Finally, we write the estimates to our database such that we can use them in later chapters.

dbWriteTable(

tidy_finance,

"beta",

value = beta,

overwrite = TRUE

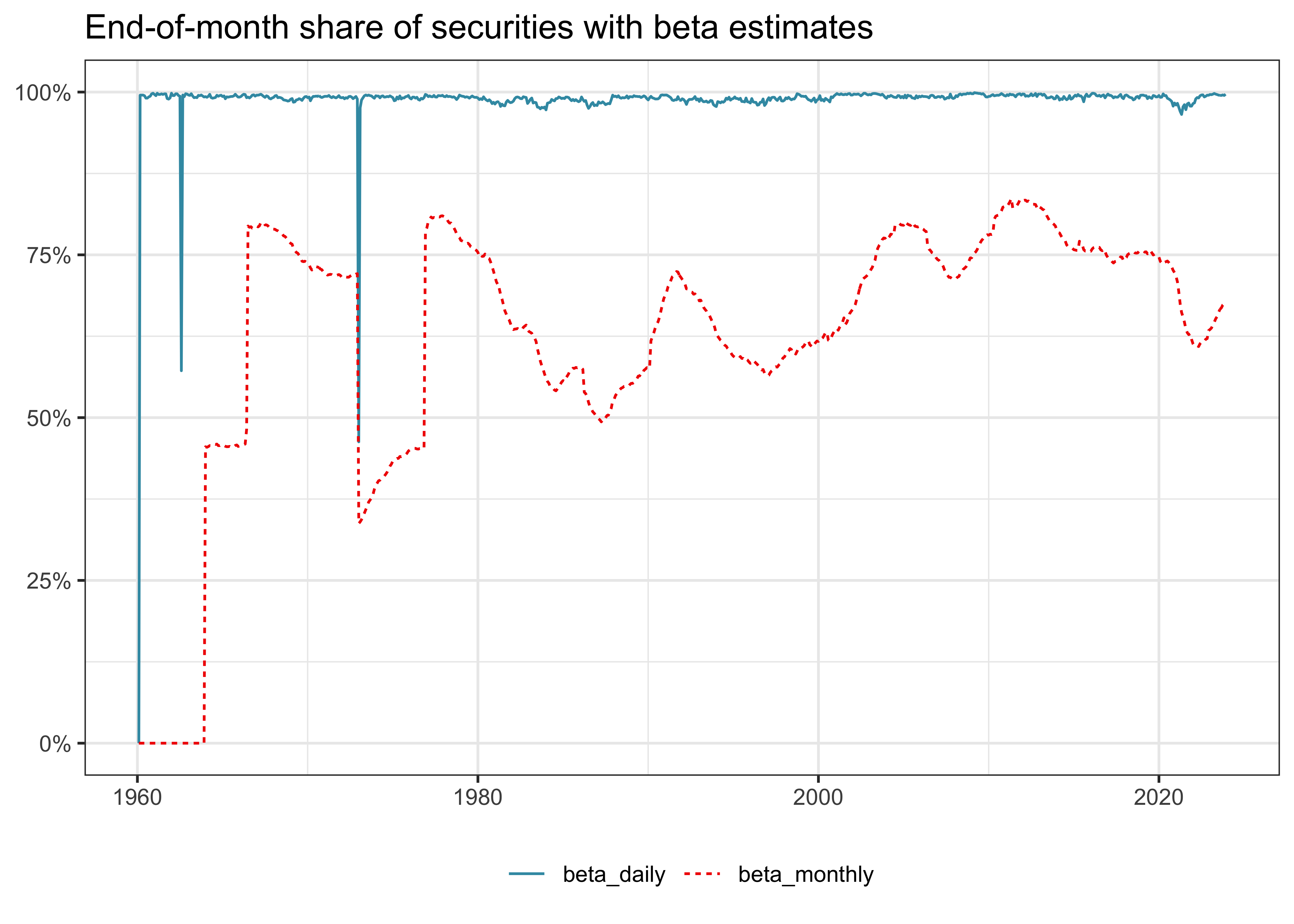

)Whenever you perform some kind of estimation, it also makes sense to do rough plausibility tests. A possible check is to plot the share of stocks with beta estimates over time. This descriptive helps us discover potential errors in our data preparation or estimation procedure. For instance, suppose there was a gap in our output where we do not have any betas. In this case, we would have to go back and check all previous steps to find out what went wrong.

beta_long <- crsp_monthly |>

left_join(beta, join_by(permno, date)) |>

pivot_longer(cols = c(beta_monthly, beta_daily))

beta_long |>

group_by(date, name) |>

summarize(share = sum(!is.na(value)) / n(),

.groups = "drop") |>

ggplot(aes(

x = date,

y = share,

color = name,

linetype = name

)) +

geom_line() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = percent) +

labs(

x = NULL, y = NULL, color = NULL, linetype = NULL,

title = "End-of-month share of securities with beta estimates"

) +

coord_cartesian(ylim = c(0, 1))Figure 5 does not indicate any troubles, so let us move on to the next check.

We also encourage everyone to always look at the distributional summary statistics of variables. You can easily spot outliers or weird distributions when looking at such tables.

beta_long |>

select(name, value) |>

drop_na() |>

group_by(name) |>

summarize(

mean = mean(value),

sd = sd(value),

min = min(value),

q05 = quantile(value, 0.05),

q50 = quantile(value, 0.50),

q95 = quantile(value, 0.95),

max = max(value),

n = n()

)# A tibble: 2 × 9

name mean sd min q05 q50 q95 max n

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <int>

1 beta_daily 0.757 0.926 -43.7 -0.436 0.694 2.23 56.6 3341630

2 beta_monthly 1.10 0.713 -13.0 0.129 1.04 2.32 11.8 2170077The summary statistics also look plausible for the two estimation procedures.

Finally, since we have two different estimators for the same theoretical object, we expect the estimators should be at least positively correlated (although not perfectly as the estimators are based on different sample periods and frequencies).

beta |>

select(beta_daily, beta_monthly) |>

cor(use = "complete.obs") beta_daily beta_monthly

beta_daily 1.000 0.323

beta_monthly 0.323 1.000Indeed, we find a positive correlation between our beta estimates. In the subsequent chapters, we mainly use the estimates based on monthly data, as most readers should be able to replicate them due to potential memory limitations that might arise with the daily data.

Key Takeaways

- CAPM betas can be estimated using rolling-window estimation via the

sliderpackage and processed in parallel viafurrr. - Both monthly and daily return data can be used to estimate betas with different frequencies and window lengths, depending on the application.

- Summary statistics, visualization, and plausibility checks help to validate beta estimates across time and industries.

- The

tidyfinanceR package provides a user-friendlyestimate_betas()function that simplifies the full beta estimation pipeline.

Exercises

- Compute beta estimates based on monthly data using one, three, and five years of data and impose a minimum number of observations of 10, 28, and 48 months with return data, respectively. How strongly correlated are the estimated betas?

- Compute beta estimates based on monthly data using five years of data and impose different numbers of minimum observations. How does the share of

permno-dateobservations with successful beta estimates vary across the different requirements? Do you find a high correlation across the estimated betas? - Instead of using

future_map(), perform the beta estimation in a loop (using either monthly or daily data) for a subset of 100 permnos of your choice. Verify that you get the same results as with the parallelized code from above. - Filter out the stocks with negative betas. Do these stocks frequently exhibit negative betas, or do they resemble estimation errors?

- Compute beta estimates for multi-factor models such as the Fama-French three-factor model. For that purpose, you extend your regression to \[ r_{i, t} - r_{f, t} = \alpha_i + \sum\limits_{j=1}^k\beta_{i,k}(r_{j, t}-r_{f,t})+\varepsilon_{i, t} \tag{1}\] where \(r_{i, t}\) are the \(k\) factor returns. Thus, you estimate four parameters (\(\alpha_i\) and the slope coefficients). Provide some summary statistics of the cross-section of firms and their exposure to the different factors.

- Estimate market betas based on daily CRSP using the

estimate_betas()function from thetidyfinancepackage. Note that a memory-efficient way is to adjust the loop that we use above to handle daily CRSP data.