library(tidyverse)

library(tidyfinance)

library(RSQLite)

library(readxl)

library(janitor)In this blog post, we show how to obtain and analyze shareholder proposal voting data for publicly listed firms in the US. For context, the SEC allows shareholders to submit proposals a few months before the annual general meeting (AGM), and these proposals end up on the ballot and are voted on if (1) a firm’s management does not submit a ‘no-action request’ accepted by the SEC or (2) management and shareholders do not reach an agreement prior to the AGM. Voting outcomes are non-binding, but management usually experiences pressure from organizations such as the Council of Institutional Investors (CII) if they do not adequately act on a proposal’s voting outcome (Bach and Metzger 2017). We refer to data provided by Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), which gained popularity as one of the major US proxy advisors. A proxy advisor provides recommendations to institutional investors on how to vote on proposals at AGMs, and in this context, ISS has used its advantageous position to build an extensive database that collects information on management and shareholder proposals.

Our code relies on the following R packages.

Data Preparation

We start by establishing a connection to WRDS using the tidyfinance package (you can find more information here) to query the data directly through their servers. We also load stocks’ identifying information to match ISS identifiers (8-digit CUSIPs) with CRSP PERMNOs. Finally, we read in an Excel file containing granular ESG-type categorization of proposal types, which is separately provided by ISS.

wrds <- get_wrds_connection()Add Variables on Vote Outcomes

As we are dealing with shareholder proposal voting data, our main interest is, of course, the voting outcome, which we determine by computing vote shares. Firms define voting rules in their corporate charters, and the variable base informs us about the voting rule that applies to a specific observation in our sample. One primarily distinguishes two cases: either abstentions are counted as votes against the proposal (base == "F+A+AB"), or they are simply ignored (base == "F+A"). We need to be careful with the values in base since the voting rules are spelled inconsistently. Two additional, though unpopular, voting categories need to be accounted for: "Outstanding" and "Capital Represe". These require dividing the votes in favor of the proposals by the total number of shares outstanding.

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

mutate(vote_share = case_when(base %in% c("F+A", "F A") ~ votedfor / (votedfor + votedagainst),

base %in% c("F+A+AB", "F A AB") ~ votedfor / (votedfor + votedagainst + votedabstain),

base %in% c("Outstanding", "Capital Represe") ~ votedfor / outstandingshare,

.default = NA))As pointed out by Cunat, Giné, and Guadalupe (2020), early studies mainly used a so-called simple majority rule, which translates into dividing votes in favor of the proposal by votes against the proposal. The reason is that earlier versions of the ISS database did not contain specific information on the voting rules defined in corporate charters but only provided votes in favor versus votes against a proposal. To be able to replicate prior results, we add a variable that computes the simple voting rule, which will collapse to the sophisticated voting rule if firms use votedfor / votedagainst (i.e., base == "F+A"). Next, we determine whether a proposal passed by comparing the vote share with the vote requirement.3 If the vote share exceeds the vote requirement, we assign a value equal to one and zero otherwise.

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

mutate(vote_share_simple = votedfor / (votedfor + votedagainst))

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

mutate(pass = if_else(vote_share >= voterequirement, 1, 0),

pass_simple = if_else(vote_share_simple >= voterequirement, 1, 0))We also compute the absolute distance of the vote share to the majority threshold.

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

mutate(distance_threshold = abs(voterequirement - vote_share),

distance_threshold_simple = abs(voterequirement - vote_share_simple))We detected a few obvious data errors, which we account for by applying some additional cleaning steps. We require that proposals must have received at least one vote, no matter whether for or against, and that base is unequal to Votes Represent because we are not sure what this voting rule refers to.

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

filter(votedfor + votedagainst > 0) |>

filter(base != "Votes Represent")We also make sure to exclude proposals for which we cannot properly compute vote shares.

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

filter(!is.na(vote_share) | !is.na(vote_share_simple),

!is.na(voterequirement))Proposal Classification

For most analyses, we want to know the reason for the proposal’s submission, or more precisely, what is actually voted on at AGMs. For that matter, ISS divides proposals into two resolution types, governance (GOV) and socially responsible investing (SRI), but also provides a more detailed categorization within GOV and SRI (see variable issagendaitemid). We refer to this more granular categorization and additionally rely on He, Kahraman, and Lowry (2023), who check and classify proposals manually to ensure we correctly capture proposals that are related to the issues we would like to analyze. ISS separately provides broad ESG-type classifications that can be linked to issagendaitemid. The respective Excel file containing the ESG classifications can be downloaded from WRDS (in the subsequent code, this file is ISSAgendaCodes_2023_All_Codes.xlsx).

iss_agenda_ids <- read_excel("ISSAgendaCodes_2023_All_Codes.xlsx") |>

clean_names() |>

mutate(agenda_esg_type = gsub("[^a-zA-Z]", "", proposal_class)) |>

select(agenda_code, agenda_esg_type)

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

left_join(iss_agenda_ids,

join_by(issagendaitemid == agenda_code))One additional comment on proposal classification is in order. As He, Kahraman, and Lowry (2023) investigate ISS resolution types, they find that not all proposals labeled as SRI (GOV) actually deal with issues related to SRI (GOV). Hence, one should be cautious when using ISS resolution types and issagendaitemid without additional checks. In their online appendix, He, Kahraman, and Lowry (2023) provide a list of issagendaitemid that actually reflects proposal types related to ecological and social issues, which allows us to gain more confidence in the classification. In the past, researchers have primarily relied on the coarse resolution type classification by ISS Flammer (2015), which introduces a potential source for replication failures when using more sophisticated classification procedures instead.

As the resolution type variable is only available in the Shareholder Proposals table, we now also extract unique pairs of resolution type and issagendaitemid from this dataset. We match these to our Vote Results table. Since it is possible that a given issagendaitemid refers to both GOV and SRI, we remove issagendaitemids that correspond to both, GOV and SRI. We document that this is only the case for id S0810 in the dataset at hand.

va_shareholder <- tbl(wrds, I("iss_va_shareholder.va_proposals")) |>

distinct(issagendaitemid, resolution_type) |>

collect() |>

drop_na()

va_shareholder |>

group_by(issagendaitemid) |>

summarize(n = n_distinct(resolution_type),

.groups = "drop") |>

filter(n > 1)# A tibble: 1 × 2

issagendaitemid n

<chr> <int>

1 S0810 2resolution_types <- va_shareholder |>

filter(issagendaitemid != "S0810")

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

left_join(resolution_types,

join_by(issagendaitemid))We have substantially manipulated the raw data, and to keep things tractable, we now make sure to keep only relevant variables for further analysis.

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

select(cusip, name, ticker,

date = meetingdate, recorddate,

meetingid, itemonagendaid,

agenda_esg_type, issagendaitemid, agendageneraldesc, itemdesc,

voterequirement, vote_share, vote_share_simple,

distance_threshold, distance_threshold_simple, pass, pass_simple)Confounding Proposal Identification

Assume that we aim to explore the effect of passing close-vote ecological and social proposals, i.e., those that have passed or failed close to the majority threshold, on expected and realized returns. In this case, Cuñat, Gine, and Guadalupe (2012) and Flammer (2015) correctly point out that there are possibly multiple close-vote proposals per AGM. It is straightforward to account for these proposals if they are also related to ecological or social concerns from an econometric point of view. However, if confounding proposals are of type governance, it becomes infeasible to disentangle the effects of close-vote governance versus close-vote ecological and social proposals on expected and realized returns. We decide to construct count variables that inform us about the number of confounding close-vote proposals (at different distances to the threshold: 5%, 10%, and 20%, respectively) that are not ecologically or socially related. Later, this procedure allows us to run robustness checks by excluding AGMs that had close-vote governance proposals in addition to close-vote ecological or social proposals.

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

group_by(cusip, date) |>

mutate(confounding_close_votes_five =

sum(distance_threshold <= 0.05 & !(agenda_esg_type %in% c("E", "S", "ES"))),

confounding_close_votes_ten =

sum(distance_threshold <= 0.1 & !(agenda_esg_type %in% c("E", "S", "ES"))),

confounding_close_votes_twenty =

sum(distance_threshold <= 0.2 & !(agenda_esg_type %in% c("E", "S", "ES")))) |>

ungroup()Matching with Other Data Sources

To conduct meaningful analyses, we must link shareholder proposal voting outcomes from ISS with other data sources such as CRSP or Compustat. In what follows, we provide code and describe how to match ISS identifiers with CRSP identifiers.

va_vote_results <- va_vote_results |>

mutate(cusip6 = substr(cusip, 1, 6),

cusip8 = substr(cusip, 1, 8)) |>

rowid_to_column("id")Before the actual matching can be performed, we need to prepare a linking table based on the Security Information History table and the Company Names table from CRSP.

stksecurityinfohist_db <- tbl(wrds, I("crsp.stksecurityinfohist"))

stksecurityinfohist <- stksecurityinfohist_db |>

mutate(cusip6 = substr(cusip, 1, 6),

cusip8 = cusip) |>

select(secinfostartdt, secinfoenddt,

permno, cusip6, cusip8, cusip9, ticker) |>

filter(!is.na(cusip8) | !is.na(ticker)) |>

collect()

stocknames_db <- tbl(wrds, I("crsp.stocknames"))

stocknames <- stocknames_db |>

select(namedt, nameenddt,

permno, comnam) |>

collect()

linking_table <- stksecurityinfohist |>

full_join(stocknames,

join_by(permno == permno,

overlaps(secinfostartdt, secinfoenddt,

namedt, nameenddt))) |>

mutate(start_date = pmax(secinfostartdt, namedt, na.rm = TRUE),

end_date = pmin(secinfoenddt, nameenddt, na.rm = TRUE)) |>

select(permno, contains("cusip"), ticker, comnam, start_date, end_date) |>

distinct()In the first step, we match ISS CUSIPs with 8- and 6-digit CUSIPs from CRSP. In case there is no appropriate match using CUSIPs, we continue the matching procedure based on standardized company names and tickers. Finally, we check for potential backward-filling in the ISS data by using a forward-looking name/CUSIP/ticker combination. Overall, we can match most shareholder proposals from ISS with CRSP identifying information following our procedure.4

matched_va_vote_results <- bind_rows(

va_vote_results,

va_vote_results |>

inner_join(linking_table |>

select(start_date, end_date, cusip8, permno) |>

drop_na() |>

distinct(),

join_by(between(date, start_date, end_date),

cusip8 == cusip8)) |>

select(-start_date, -end_date) |>

mutate(match = 1),

va_vote_results |>

inner_join(linking_table |>

select(start_date, end_date, cusip6, permno) |>

drop_na() |>

distinct(),

join_by(between(date, start_date, end_date),

cusip6 == cusip6)) |>

select(-start_date, -end_date) |>

mutate(match = 2),

va_vote_results |> # match on name

mutate(check_name = substr(tolower(gsub("[^a-zA-Z]", "", name)), 1, 10)) |>

inner_join(linking_table |>

mutate(comnam = substr(tolower(gsub("[^a-zA-Z]", "", comnam)), 1, 10)) |>

select(start_date, end_date, comnam, permno) |>

drop_na() |>

distinct(),

join_by(between(date, start_date, end_date),

check_name == comnam)) |>

select(-start_date, -end_date, -check_name) |>

mutate(match = 3),

va_vote_results |>

inner_join(linking_table |>

select(start_date, end_date, ticker, permno) |>

drop_na() |>

distinct(),

join_by(between(date, start_date, end_date),

ticker == ticker)) |>

select(-start_date, -end_date) |>

mutate(match = 4),

va_vote_results |>

mutate(check_name = substr(tolower(gsub("[^a-zA-Z]", "", name)), 1, 10)) |>

inner_join(linking_table |>

mutate(comnam = substr(tolower(gsub("[^a-zA-Z]", "", comnam)), 1, 10)) |>

select(comnam, cusip8, ticker, permno) |>

drop_na() |>

distinct(),

join_by(check_name == comnam,

cusip8 == cusip8,

ticker == ticker)) |>

select(-check_name) |>

mutate(match = 5))

matched_va_vote_results <- matched_va_vote_results |>

arrange(match) |>

group_by(id) |>

slice_head(n = 1) |>

ungroup() |>

select(-id, -cusip6, -cusip8, -match)Coverage

Following our proposed procedure, out of 13,952 proposals after our cleaning steps, we end up with a sample of 13,603 shareholder proposals in total (that can be matched to CRSP) spanning a period from 2002 to 2024.

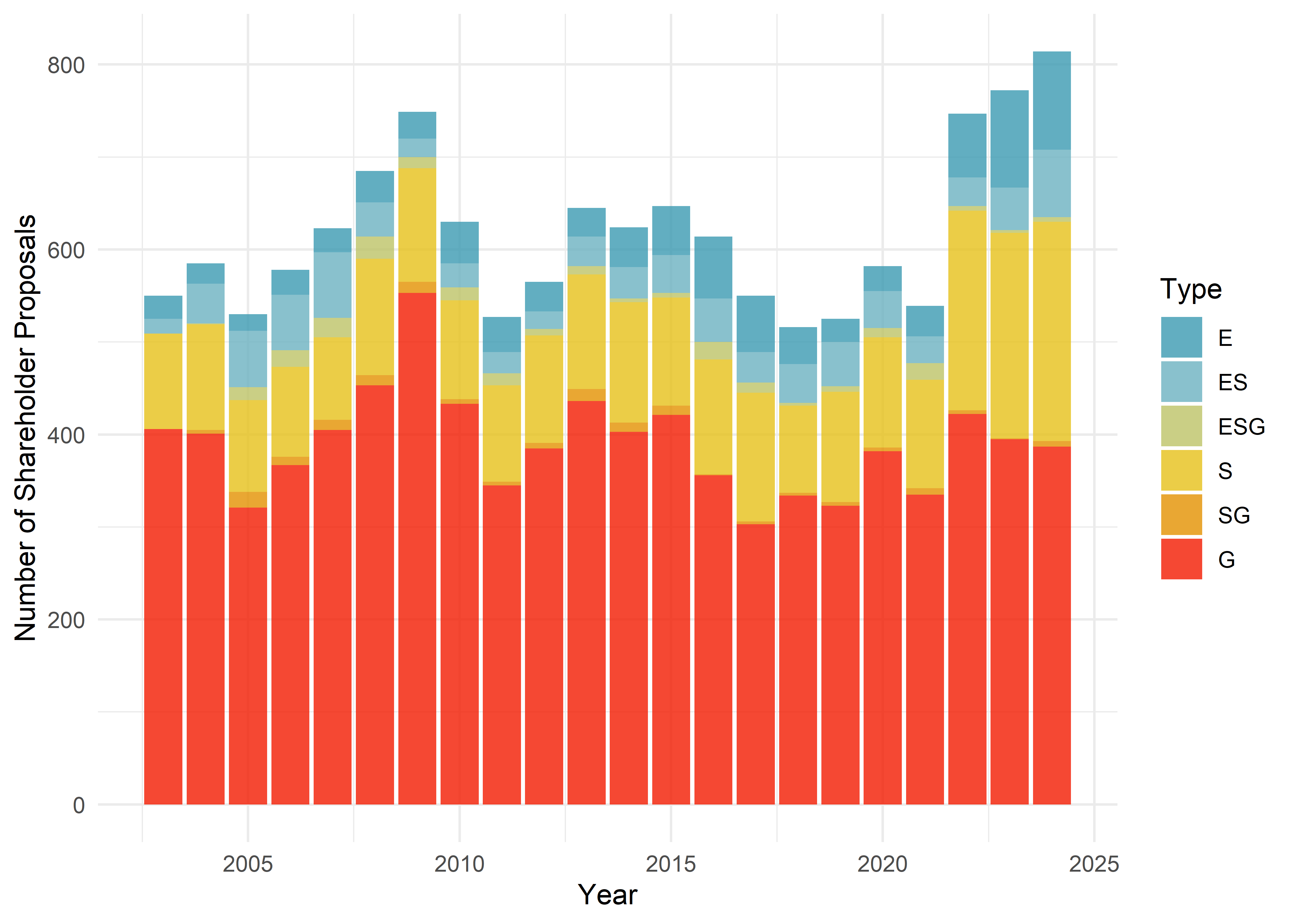

In the following plot, we show the number of proposals over time grouped by ESG type.

Following the ESG-type classification of ISS, the share of proposals focused on ecological and social issues hardly changes over most parts of the sample period but experiences a spike in recent years (2022 - 2024). This might come as a surprise, considering how environmental and sustainability considerations have already shaped the investment industry throughout the last decade. On the other hand, taking into account that governance-type proposals cover “standard topics” such as shareholder rights or issues related to the board of directors, it should be no surprise that this group makes up the largest fraction of proposals throughout.

In the next plot, we take a closer look at the distribution of the vote share across different proposal classifications.

Most proposals related to ecological and social issues fail, and they usually do so by large margins as the majority threshold is commonly set to 50%. However, for governance proposals, the distribution looks quite different. Their vote shares are way more balanced, and there is no clear tendency for proposal failure. The observed pattern suggests that investors are more skeptical of ecological and social proposals than governance proposals.

Extensions on the Data

The ISS Voting Analytics data is most widely used in empirical finance research studies when it comes to shareholder proposals and proxy voting. Nevertheless, we would like to mention that there are other sources for voting data on shareholder proposals as well. One other prominent source is FactSet, which provides voting data for US firms in the dataset “Proxy Proposals & N-PX”. This database was previously known as SharkRepellent and was acquired by FactSet in 2005.5 Currently, we do not have access to this data, but judging by studies that use ISS and FactSet (see, e.g., Flammer 2015) jointly, there seems to be a substantial amount of proposals that are either covered by ISS or FactSet. This implies that one can significantly increase overall sample sizes by drawing from both sources.

If one wishes to analyze European shareholder proposal voting data, we refer to the Company Vote Results Global database by ISS. Here, data is available for non-US companies from 2013 onward.

References

Footnotes

A typical example of a management proposal is the election of new board members.↩︎

Upon request, ISS also provides legacy data going back until 1997.↩︎

Typically, the vote requirement equals 50%. Note, however, that there are also exceptions, e.g., when shareholders elect new board members. This is often a pro forma vote with a minuscule threshold.↩︎

Note that we recommend checking unmatched proposals manually and assigning identifying information if available, as the total number of unmatched proposals is manageable.↩︎